*rpp, Reading 70, Rawls, a Theory of Justice

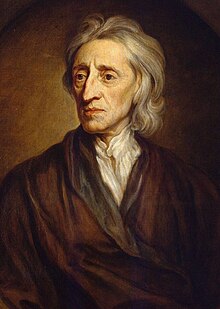

| John Locke FRS | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Locke in 1697 by Godfrey Kneller | |

| Born | John Locke (1632-08-29)29 August 1632 Wrington, Somerset, England |

| Died | 28 Oct 1704(1704-ten-28) (aged 72) High Laver, Essex, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Oxford University (B.A., 1656; M.A., 1658; Thou.B., 1675) |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions | Christ Church, Oxford[7] Regal Society |

| Master interests | Metaphysics, epistemology, political philosophy, philosophy of mind, philosophy of educational activity, economics |

| Notable ideas | List

|

| Influences

| |

| Influenced

| |

| Signature | |

| |

John Locke'due south portrait past Godfrey Kneller, National Portrait Gallery, London

John Locke FRS (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and md, widely regarded as i of the virtually influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known every bit the "Begetter of Liberalism".[12] [13] [14] Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Sir Francis Bacon, Locke is as important to social contract theory. His work greatly affected the development of epistemology and political philosophy. His writings influenced Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well equally the American Revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the Usa Annunciation of Independence.[fifteen] Internationally, Locke's political-legal principles keep to accept a profound influence on the theory and practice of limited representative authorities and the protection of basic rights and freedoms nether the rule of law.[sixteen]

Locke'south theory of mind is oftentimes cited every bit the origin of modern conceptions of identity and the self, figuring prominently in the work of later on philosophers such every bit Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant. Locke was the first to ascertain the self through a continuity of consciousness. He postulated that, at birth, the heed was a blank slate, or tabula rasa. Contrary to Cartesian philosophy based on pre-existing concepts, he maintained that we are built-in without innate ideas, and that knowledge is instead determined only by experience derived from sense perception, a concept now known every bit empiricism.[17] Demonstrating the ideology of science in his observations, whereby something must be capable of existence tested repeatedly and that nothing is exempt from being disproved, Locke stated that "whatsoever I write, as soon as I discover it not to exist true, my mitt shall be the forwardest to throw it into the burn". Such is one example of Locke's belief in empiricism.

Early life

Locke was born on 29 August 1632, in a pocket-sized thatched cottage by the church in Wrington, Somerset, almost 12 miles from Bristol. He was baptised the same day, as both of his parents were Puritans. Locke'due south father, also called John, was an attorney who served every bit clerk to the Justices of the Peace in Chew Magna[18] and as a helm of cavalry for the Parliamentarian forces during the early function of the English Ceremonious State of war. His mother was Agnes Keene. Soon afterwards Locke'southward birth, the family moved to the marketplace town of Pensford, most seven miles due south of Bristol, where Locke grew up in a rural Tudor house in Belluton.

In 1647, Locke was sent to the prestigious Westminster School in London under the sponsorship of Alexander Popham, a member of Parliament and John Sr.'s erstwhile commander. After completing studies at that place, he was admitted to Christ Church building, Oxford, in the autumn of 1652 at the age of 20. The dean of the college at the time was John Owen, vice-chancellor of the academy. Although a capable student, Locke was irritated by the undergraduate curriculum of the time. He plant the works of modern philosophers, such equally René Descartes, more interesting than the classical cloth taught at the university. Through his friend Richard Lower, whom he knew from the Westminster Schoolhouse, Locke was introduced to medicine and the experimental philosophy being pursued at other universities and in the Regal Society, of which he eventually became a member.

Locke was awarded a bachelor'south degree in February 1656 and a primary's degree in June 1658.[7] He obtained a bachelor of medicine in Feb 1675,[19] having studied the subject area extensively during his fourth dimension at Oxford and, in add-on to Lower, worked with such noted scientists and thinkers as Robert Boyle, Thomas Willis and Robert Hooke. In 1666, he met Anthony Ashley Cooper, Lord Ashley, who had come to Oxford seeking treatment for a liver infection. Ashley was impressed with Locke and persuaded him to become part of his retinue.

Career

Work

Locke had been looking for a career and in 1667 moved into Ashley's home at Exeter Business firm in London, to serve as his personal md. In London, Locke resumed his medical studies under the tutelage of Thomas Sydenham. Sydenham had a major event on Locke's natural philosophical thinking – an effect that would become axiomatic in An Essay Apropos Human Understanding.

Locke's medical cognition was put to the test when Ashley's liver infection became life-threatening. Locke coordinated the communication of several physicians and was probably instrumental in persuading Ashley to undergo surgery (and then life-threatening itself) to remove the cyst. Ashley survived and prospered, crediting Locke with saving his life.

During this fourth dimension, Locke served as Secretarial assistant of the Lath of Trade and Plantations and Secretary to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, which helped to shape his ideas on international trade and economics.

Ashley, every bit a founder of the Whig movement, exerted great influence on Locke'southward political ideas. Locke became involved in politics when Ashley became Lord Chancellor in 1672 (Ashley existence created 1st Earl of Shaftesbury in 1673). Following Shaftesbury'southward fall from favour in 1675, Locke spent some time travelling beyond French republic as a tutor and medical attendant to Caleb Banks.[20] He returned to England in 1679 when Shaftesbury'south political fortunes took a brief positive plow. Around this time, almost likely at Shaftesbury's prompting, Locke composed the bulk of the Two Treatises of Government. While it was in one case thought that Locke wrote the Treatises to defend the Glorious Revolution of 1688, contempo scholarship has shown that the work was composed well earlier this engagement.[21] The work is now viewed every bit a more general statement against accented monarchy (particularly as espoused past Robert Filmer and Thomas Hobbes) and for individual consent as the basis of political legitimacy. Although Locke was associated with the influential Whigs, his ideas about natural rights and regime are today considered quite revolutionary for that flow in English history.

The Netherlands

Locke fled to the Netherlands in 1683, nether strong suspicion of involvement in the Rye Firm Plot, although there is picayune evidence to advise that he was directly involved in the scheme. The philosopher and novelist Rebecca Newberger Goldstein argues that during his five years in Holland, Locke chose his friends "from among the same freethinking members of dissenting Protestant groups as Spinoza's pocket-sized group of loyal confidants. [Baruch Spinoza had died in 1677.] Locke almost certainly met men in Amsterdam who spoke of the ideas of that renegade Jew who... insisted on identifying himself through his religion of reason alone." While she says that "Locke's strong empiricist tendencies" would have "disinclined him to read a grandly metaphysical piece of work such as Spinoza'southward Ethics, in other ways he was deeply receptive to Spinoza'due south ideas, most peculiarly to the rationalist's well thought out argument for political and religious tolerance and the necessity of the separation of church and state."[22] In kingdom of the netherlands, Locke had time to render to his writing, spending a smashing deal of time working on the Essay Concerning Human being Understanding and composing the Letter of the alphabet on Toleration.

Return to England

Locke did not return home until later the Glorious Revolution. Locke accompanied Mary Two dorsum to England in 1688. The majority of Locke's publishing took place upon his return from exile – his aforementioned Essay Apropos Man Agreement, the Two Treatises of Government and A Alphabetic character Concerning Toleration all appearing in quick succession.

Locke's close friend Lady Masham invited him to join her at Otes, the Mashams' country firm in Essex. Although his fourth dimension in that location was marked by variable health from asthma attacks, he nevertheless became an intellectual hero of the Whigs. During this menstruation he discussed matters with such figures as John Dryden and Isaac Newton.

Death

He died on 28 October 1704, and is buried in the churchyard of the village of High Laver,[23] due east of Harlow in Essex, where he had lived in the household of Sir Francis Masham since 1691. Locke never married nor had children.

Events that happened during Locke's lifetime include the English Restoration, the Corking Plague of London, the Not bad Fire of London, and the Glorious Revolution. He did non quite come across the Act of Union of 1707, though the thrones of England and Scotland were held in personal spousal relationship throughout his lifetime. Constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy were in their infancy during Locke'southward time.

Philosophy

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Locke'due south Two Treatises were rarely cited. Historian Julian Hoppit said of the volume, "except among some Whigs, even as a contribution to the intense contend of the 1690s it made trivial impression and was generally ignored until 1703 (though in Oxford in 1695 it was reported to have made 'a bully noise')."[24] John Kenyon, in his study of British political debate from 1689 to 1720, has remarked that Locke's theories were "mentioned so rarely in the early stages of the [Glorious] Revolution, upward to 1692, and even less thereafter, unless it was to heap abuse on them" and that "no i, including most Whigs, [was] fix for the idea of a notional or abstract contract of the kind adumbrated past Locke".[25] : 200 In contrast, Kenyon adds that Algernon Sidney'southward Discourses Concerning Government were "certainly much more than influential than Locke's Two Treatises."[i] [25] : 51

In the 50 years after Queen Anne'south death in 1714, the Ii Treatises were reprinted only one time (except in the collected works of Locke). Yet, with the rise of American resistance to British tax, the Second Treatise of Government gained a new readership; it was frequently cited in the debates in both America and Great britain. The start American press occurred in 1773 in Boston.[26]

Locke exercised a profound influence on political philosophy, in particular on modern liberalism. Michael Zuckert has argued that Locke launched liberalism past tempering Hobbesian absolutism and conspicuously separating the realms of Church and State. He had a strong influence on Voltaire, who called him "le sage Locke". His arguments concerning liberty and the social contract subsequently influenced the written works of Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and other Founding Fathers of the United States. In fact, one passage from the Second Treatise is reproduced verbatim in the Declaration of Independence, the reference to a "long train of abuses". Such was Locke's influence that Thomas Jefferson wrote:[27] [28] [29]

Bacon, Locke and Newton… I consider them as the 3 greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which take been raised in the Concrete and Moral sciences.

Withal, Locke's influence may have been fifty-fifty more profound in the realm of epistemology. Locke redefined subjectivity, or self, leading intellectual historians such as Charles Taylor and Jerrold Seigel to contend that Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689/90) marks the get-go of the modern Western formulation of the self.[30] [31]

Locke's theory of association heavily influenced the subject matter of modern psychology. At the fourth dimension, Locke'south recognition of two types of ideas, simple and circuitous—and, more importantly, their interaction through association—inspired other philosophers, such as David Hume and George Berkeley, to revise and expand this theory and utilize it to explain how humans gain noesis in the concrete world.[32]

Religious tolerance

Writing his Letters Concerning Toleration (1689–1692) in the aftermath of the European wars of religion, Locke formulated a classic reasoning for religious tolerance, in which three arguments are central:[33]

- earthly judges, the state in particular, and human beings more often than not, cannot dependably evaluate the truth-claims of competing religious standpoints;

- even if they could, enforcing a unmarried 'truthful religion' would non accept the desired consequence, because belief cannot be compelled past violence;

- coercing religious uniformity would lead to more social disorder than assuasive diversity.

With regard to his position on religious tolerance, Locke was influenced by Baptist theologians like John Smyth and Thomas Helwys, who had published tracts demanding freedom of conscience in the early 17th century.[34] [35] [36] [37] Baptist theologian Roger Williams founded the colony of Rhode Isle in 1636, where he combined a democratic constitution with unlimited religious freedom. His tract, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Crusade of Censor (1644), which was widely read in the mother country, was a passionate plea for absolute religious liberty and the full separation of church and state.[38] Liberty of conscience had had loftier priority on the theological, philosophical, and political agenda, as Martin Luther refused to recant his beliefs before the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire at Worms in 1521, unless he would be proved false past the Bible.[39]

Slavery and child labour

Locke's views on slavery were multifaceted and complex. Although he wrote against slavery in general, Locke was an investor and beneficiary of the slave trading Purple Africa Company. In add-on, while secretary to the Earl of Shaftesbury, Locke participated in drafting the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which established a quasi-feudal aristocracy and gave Carolinian planters absolute power over their enslaved chattel belongings; the constitutions pledged that "every freeman of Carolina shall accept absolute power and authorization over his negro slaves". Philosopher Martin Cohen notes that Locke, every bit secretarial assistant to the Council of Merchandise and Plantations and a member of the Board of Trade, was "1 of just one-half a dozen men who created and supervised both the colonies and their iniquitous systems of servitude".[40] [41] According to American historian James Farr, Locke never expressed any thoughts concerning his contradictory opinions regarding slavery, which Farr ascribes to his personal involvement in the slave trade.[42] Locke'due south positions on slavery have been described equally hypocritical, and laying the foundation for the Founding Fathers to hold similarly contradictory thoughts regarding freedom and slavery.[43] Locke also drafted implementing instructions for the Carolina colonists designed to ensure that settlement and development was consequent with the Fundamental Constitutions. Collectively, these documents are known every bit the Thou Model for the Province of Carolina.[ commendation needed ]

Historian Holly Brewer has argued, all the same, that Locke'southward office in the Constitution of Carolina has been exaggerated and that he was merely paid to revise and brand copies of a document that had already been partially written before he became involved; she compares Locke's role to a lawyer writing a will.[44] She further notes that Locke was paid in Royal African Company stock in lieu of money for his piece of work every bit a secretary for a governmental sub-commission and that he sold the stock after but a few years.[45] Brewer also argues that Locke actively worked to undermine slavery in Virginia while heading a Board of Merchandise created past William of Orangish following the Glorious Revolution. He specifically attacked colonial policy granting country to slave owners and encouraged the baptism and Christian pedagogy of the children of enslaved Africans to undercut a major justification of slavery—that they were heathens that possessed no rights.[46]

Locke also supported kid labour. In his "Essay on the Poor Law", he turns to the didactics of the poor; he laments that "the children of labouring people are an ordinary burden to the parish, and are usually maintained in idleness, so that their labour also is more often than not lost to the public till they are 12 or 14 years old".[47] : 190 He suggests, therefore, that "working schools" be fix upward in each parish in England for poor children and then that they will exist "from infancy [iii years old] inured to work".[47] : 190 He goes on to outline the economic science of these schools, arguing non but that they will be assisting for the parish, but also that they volition instill a skillful work ethic in the children.[47] : 191

Government

Locke'southward political theory was founded upon that of social contract. Different Thomas Hobbes, Locke believed that human nature is characterised past reason and tolerance. Like Hobbes, however, Locke believed that man nature allows people to exist selfish. This is credible with the introduction of currency. In a natural state, all people were equal and independent, and everyone had a natural right to defend his "life, health, liberty, or possessions".[48] : 198 Well-nigh scholars trace the phrase "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness" in the American Declaration of Independence to Locke's theory of rights,[49] although other origins take been suggested.[50]

Like Hobbes, Locke assumed that the sole right to defend in the state of nature was not plenty, and then people established a ceremonious social club to resolve conflicts in a civil way with help from government in a state of lodge. However, Locke never refers to Hobbes by proper noun and may instead accept been responding to other writers of the day.[51] Locke as well advocated governmental separation of powers and believed that revolution is not only a right only an obligation in some circumstances. These ideas would come up to have profound influence on the Proclamation of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.

Aggregating of wealth

Co-ordinate to Locke, unused property is wasteful and an offence confronting nature,[52] but, with the introduction of "durable" goods, men could exchange their excessive perishable goods for those which would last longer and thus not offend the natural constabulary. In his view, the introduction of money marked the culmination of this process, making possible the unlimited accumulation of property without causing waste through spoilage.[53] He besides includes gilded or silver equally coin because they may be "hoarded up without injury to anyone",[54] as they do not spoil or decay in the easily of the possessor. In his view, the introduction of coin eliminates limits to accumulation. Locke stresses that inequality has come virtually by tacit agreement on the use of money, not by the social contract establishing civil society or the law of land regulating belongings. Locke is aware of a problem posed by unlimited accumulation, but does not consider information technology his chore. He just implies that government would function to moderate the conflict betwixt the unlimited aggregating of property and a more nigh equal distribution of wealth; he does not identify which principles that government should apply to solve this problem. Notwithstanding, not all elements of his idea class a consequent whole. For example, the labour theory of value in the Two Treatises of Government stands side by side with the demand-and-supply theory of value developed in a letter he wrote titled Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Involvement and the Raising of the Value of Money. Moreover, Locke anchors property in labour but, in the finish, upholds unlimited aggregating of wealth.[55]

Other Ideas

Economics

On price theory

Locke'south general theory of value and price is a supply-and-demand theory, set out in a letter to a member of parliament in 1691, titled Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money.[56] In it, he refers to supply equally quantity and demand as rent: "The toll of any commodity rises or falls past the proportion of the number of buyers and sellers" and "that which regulates the cost…[of goods] is nothing else but their quantity in proportion to their rent."

The quantity theory of coin forms a special instance of this general theory. His thought is based on "money answers all things" (Ecclesiastes) or "rent of money is e'er sufficient, or more than enough" and "varies very picayune". Locke concludes that, as far every bit money is concerned, the demand for it is exclusively regulated past its quantity, regardless of whether the demand is unlimited or constant. He also investigates the determinants of demand and supply. For supply, he explains the value of goods as based on their scarcity and ability to be exchanged and consumed. He explains need for goods as based on their ability to yield a flow of income. Locke develops an early theory of capitalisation, such as of land, which has value considering "past its constant product of saleable commodities it brings in a certain yearly income". He considers the demand for money equally virtually the same as demand for goods or land: it depends on whether coin is wanted as medium of exchange. Every bit a medium of exchange, he states, "money is capable by exchange to procure us the necessaries or conveniences of life" and, for loanable funds, "it comes to be of the same nature with country by yielding a sure yearly income…or interest".

Monetary thoughts

Locke distinguishes two functions of money: as a counter to measure value, and as a pledge to lay claim to goods. He believes that silver and gold, every bit opposed to paper money, are the appropriate currency for international transactions. Silver and gold, he says, are treated to have equal value by all of humanity and can thus be treated as a pledge by anyone, while the value of paper money is only valid under the government which bug it.

Locke argues that a country should seek a favourable balance of merchandise, lest it fall behind other countries and suffer a loss in its trade. Since the world coin stock grows constantly, a country must constantly seek to enlarge its ain stock. Locke develops his theory of foreign exchanges, in addition to commodity movements, there are also movements in country stock of money, and movements of upper-case letter decide exchange rates. He considers the latter less pregnant and less volatile than commodity movements. As for a country's coin stock, if information technology is big relative to that of other countries, he says information technology will cause the country's exchange to rise in a higher place par, as an export residue would do.

He also prepares estimates of the cash requirements for different economic groups (landholders, labourers, and brokers). In each group he posits that the greenbacks requirements are closely related to the length of the pay flow. He argues the brokers—the middlemen—whose activities enlarge the monetary circuit and whose profits eat into the earnings of labourers and landholders, take a negative influence on both personal and the public economy to which they supposedly contribute.

Theory of value and holding

Locke uses the concept of property in both wide and narrow terms: broadly, it covers a wide range of human interests and aspirations; more particularly, it refers to fabric appurtenances. He argues that property is a natural right that is derived from labour. In Affiliate Five of his Second Treatise, Locke argues that the private ownership of goods and property is justified past the labour exerted to produce such goods—"at to the lowest degree where there is enough [country], and every bit good, left in common for others" (para. 27)—or to utilize property to produce goods benign to human society.[57]

Locke states in his 2d Treatise that nature on its own provides little of value to society, implying that the labour expended in the creation of appurtenances gives them their value. From this premise, understood as a labour theory of value,[57] Locke developed a labour theory of property, whereby ownership of property is created by the application of labour. In addition, he believed that property precedes regime and government cannot "dispose of the estates of the subjects arbitrarily". Karl Marx later critiqued Locke'southward theory of property in his own social theory.[ citation needed ]

The human mind

The cocky

Locke defines the self as "that conscious thinking thing, (whatever substance, fabricated upwards of whether spiritual, or material, simple, or compounded, it matters not) which is sensible, or witting of pleasance and pain, capable of happiness or misery, and then is concerned for itself, every bit far as that consciousness extends".[58] He does not, nevertheless, wholly ignore "substance", writing that "the body too goes to the making the man".[59]

In his Essay, Locke explains the gradual unfolding of this conscious mind. Arguing against both the Augustinian view of homo as originally sinful and the Cartesian position, which holds that human innately knows basic logical propositions, Locke posits an 'empty mind', a tabula rasa, which is shaped past experience; sensations and reflections being the two sources of all of our ideas.[60] He states in An Essay Apropos Human Agreement:

This source of ideas every homo has wholly within himself; and though it be non sense, as having naught to do with external objects, yet information technology is very similar it, and might properly enough be chosen 'internal sense.'[61]

Locke'due south Some Thoughts Apropos Pedagogy is an outline on how to brainwash this mind. Drawing on thoughts expressed in letters written to Mary Clarke and her husband nigh their son,[62] he expresses the belief that education makes the man—or, more fundamentally, that the mind is an "empty chiffonier":[63]

I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, 9 parts of 10 are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their educational activity.

Locke also wrote that "the lilliputian and almost insensible impressions on our tender infancies have very important and lasting consequences".[63] He argues that the "associations of ideas" that one makes when young are more important than those made later because they are the foundation of the cocky; they are, put differently, what first mark the tabula rasa. In his Essay, in which both these concepts are introduced, Locke warns, for example, against letting "a foolish maid" convince a child that "goblins and sprites" are associated with the night, for "darkness shall ever later bring with information technology those frightful ideas, and they shall be and then joined, that he can no more bear the one than the other".[64]

This theory came to exist called associationism, going on to strongly influence 18th-century thought, particularly educational theory, as well-nigh every educational writer warned parents not to allow their children to develop negative associations. It also led to the development of psychology and other new disciplines with David Hartley's endeavour to discover a biological machinery for associationism in his Observations on Human being (1749).

Dream argument

Locke was critical of Descartes' version of the dream statement, with Locke making the counter-argument that people cannot have physical pain in dreams equally they do in waking life.[65]

Organized religion

Religious beliefs

Some scholars have seen Locke'due south political convictions as being based from his religious behavior.[66] [67] [68] Locke's religious trajectory began in Calvinist trinitarianism, just by the time of the Reflections (1695) Locke was advocating not simply Socinian views on tolerance but also Socinian Christology.[69] Still Wainwright (1987) notes that in the posthumously published Paraphrase (1707) Locke's interpretation of ane verse, Ephesians 1:ten, is markedly unlike from that of Socinians like Biddle, and may signal that most the terminate of his life Locke returned nearer to an Arian position, thereby accepting Christ's pre-existence.[70] [69] Locke was at times not certain about the subject of original sin, so he was defendant of Socinianism, Arianism, or Deism.[71] Locke argued that the idea that "all Adam'southward Posterity [are] doomed to Eternal Space Punishment, for the Transgression of Adam" was "little consistent with the Justice or Goodness of the Slap-up and Space God", leading Eric Nelson to associate him with Pelagian ideas.[72] Nonetheless, he did not deny the reality of evil. Man was capable of waging unjust wars and committing crimes. Criminals had to be punished, even with the death sentence.[73]

With regard to the Bible, Locke was very conservative. He retained the doctrine of the verbal inspiration of the Scriptures.[34] The miracles were proof of the divine nature of the biblical message. Locke was convinced that the entire content of the Bible was in understanding with man reason (The Reasonableness of Christianity, 1695).[74] [34] Although Locke was an advocate of tolerance, he urged the government not to tolerate atheism, considering he thought the denial of God's existence would undermine the social guild and lead to anarchy.[75] That excluded all atheistic varieties of philosophy and all attempts to deduce ethics and natural law from purely secular premises.[76] In Locke'due south opinion the cosmological argument was valid and proved God's beingness. His political thought was based on Protestant Christian views.[76] [77] Additionally, Locke advocated a sense of piety out of gratitude to God for giving reason to men.[78]

Philosophy from religion

Locke'due south concept of man started with the belief in creation.[79] Like philosophers Hugo Grotius and Samuel Pufendorf, Locke equated natural law with the biblical revelation.[80] [81] [82] Locke derived the cardinal concepts of his political theory from biblical texts, in particular from Genesis 1 and 2 (creation), the Decalogue, the Golden Dominion, the teachings of Jesus, and the messages of Paul the Campaigner.[83] The Decalogue puts a person'due south life, reputation and property under God's protection.

Locke's philosophy on freedom is as well derived from the Bible. Locke derived from the Bible basic human being equality (including equality of the sexes), the starting point of the theological doctrine of Imago Dei.[84] To Locke, one of the consequences of the principle of equality was that all humans were created every bit free and therefore governments needed the consent of the governed.[85] Locke compared the English monarchy'due south dominion over the British people to Adam'due south dominion over Eve in Genesis, which was appointed by God.[86]

Following Locke'southward philosophy, the American Declaration of Independence founded human rights partially on the biblical belief in cosmos. Locke's doctrine that governments need the consent of the governed is too central to the Proclamation of Independence.[87]

Library and manuscripts

Locke's signature in Bodleian Locke thirteen.12. Photograph taken at the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Locke was an assiduous book collector and notetaker throughout his life. Past his death in 1704, Locke had amassed a library of more than than 3,000 books, a pregnant number in the seventeenth century.[88] Unlike some of his contemporaries, Locke took care to catalogue and preserve his library, and his will made specific provisions for how his library was to be distributed afterward his expiry. Locke'south volition offered Lady Masham the choice of "any 4 folios, eight quartos and twenty books of less volume, which she shall choose out of the books in my Library."[89] Locke also gave half dozen titles to his "expert friend" Anthony Collins, but Locke bequeathed the majority of his drove to his cousin Peter King (after Lord Rex) and to Lady Masham'southward son, Francis Cudworth Masham.[89]

Francis Masham was promised ane "moiety" (half) of Locke's library when he reached "the historic period of 1 and 20 years."[89] The other "moiety" of Locke'south books, along with his manuscripts, passed to his cousin Male monarch.[89] Over the next 2 centuries, the Masham portion of Locke's library was dispersed.[xc] The manuscripts and books left to Rex, however, remained with King's descendants (after the Earls of Lovelace), until most of the collection was bought past the Bodleian Library, Oxford in 1947.[91] Another portion of the books Locke left to King was discovered past the collector and philanthropist Paul Mellon in 1951.[91] Mellon supplemented this discovery with books from Locke's library which he bought privately, and in 1978, he transferred his collection to the Bodleian.[91] The holdings in the Locke Room at the Bodleian have been a valuable resource for scholars interested in Locke, his philosophy, practices for data management, and the history of the book.

The printed books in Locke's library reflected his various intellectual interests besides as his movements at different stages of his life. Locke travelled extensively in French republic and the netherlands during the 1670s and 1680s, and during this fourth dimension he acquired many books from the continent. Only half of the books in Locke'southward library were printed in England, while close to xl% came from France and the Netherlands.[92] These books embrace a wide range of subjects. According to John Harrison and Peter Laslett, the largest genres in Locke's library were theology (23.8% of books), medicine (11.1%), politics and constabulary (x.vii%), and classical literature (10.ane%).[93] The Bodleian library currently holds more 800 of the books from Locke's library.[91] These include Locke'south copies of works by several of the virtually influential figures of the seventeenth century, including

- The Quaker William Penn: An address to Protestants of all perswasions (Bodleian Locke 7.69a)

- The explorer Francis Drake: The earth encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (Bodleian Locke 8.37c)

- The scientist Robert Boyle: A discourse of things above reason (Bodleian Locke 7.272)

- The bishop and historian Thomas Sprat: The history of the Purple-Club of London (Bodleian Locke 9.10a)

Many of the books notwithstanding contain Locke'southward signature, which he oft made on the pastedowns of his books. Many besides include Locke's marginalia.

In addition to books owned by Locke, the Bodleian likewise possesses more than 100 manuscripts related to Locke or written in his hand. Similar the books in Locke's library, these manuscripts brandish a range of interests and provide different windows into Locke's activity and relationships. Several of the manuscripts include letters to and from acquaintances like Peter King (MS Locke b. 6) and Nicolas Toinard (MS Locke c. 45).[94] MS Locke f. 1–x contain Locke'due south journals for most years between 1675 and 1704.[94] Some of the most meaning manuscripts include early drafts of Locke'due south writings, such as his Essay concerning man understanding (MS Locke f. 26).[94] The Bodleian too holds a copy of Robert Boyle'south General History of the Air with corrections and notes Locke made while preparing Boyle's work for posthumous publication (MS Locke c. 37 ).[95] Other manuscripts contain unpublished works. Among others, MS. Locke e. 18 includes some of Locke's thoughts on the Glorious Revolution, which Locke sent to his friend Edward Clarke simply never published.[96]

Ane of the largest categories of manuscript at the Bodleian comprises Locke'southward notebooks and commonplace books. The scholar Richard Yeo calls Locke a "Main Annotation-taker" and explains that "Locke's methodical note-taking pervaded about areas of his life."[97] In an unpublished essay "Of Study," Locke argued that a notebook should piece of work like a "chest-of-drawers" for organizing information, which would be a "dandy assistance to the memory and ways to avert confusion in our thoughts."[98] Locke kept several notebooks and commonplace books, which he organized according to topic. MS Locke c. 43 includes Locke'south notes on theology, while MS Locke f. 18–24 incorporate medical notes.[94] Other notebooks, such as MS c. 43, incorporate several topics in the same notebook, but separated into sections.[94]

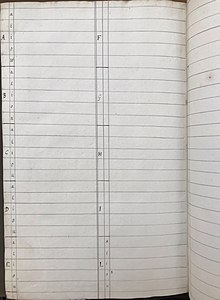

Page 1 of Locke's unfinished index in Bodleian Locke xiii.12. Photograph taken at the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

These commonplace books were highly personal and were designed to be used by Locke himself rather than attainable to a wide audience.[99] Locke'due south notes are often abbreviated and are full of codes which he used to reference textile beyond notebooks.[100] Another style Locke personalized his notebooks was by devising his ain method of creating indexes using a grid organisation and Latin keywords.[101] Instead of recording entire words, his indexes shortened words to their first letter and vowel. Thus, the word "Epistle" would be classified as "Ei".[102] Locke published his method in French in 1686, and information technology was republished posthumously in English language in 1706.

Some of the books in Locke'due south library at the Bodleian are a combination of manuscript and print. Locke had some of his books interleaved, meaning that they were bound with bare sheets in-betwixt the printed pages to enable annotations. Locke interleaved and annotated his five volumes of the New Attestation in French, Greek, and Latin (Bodleian Locke nine.103-107). Locke did the same with his copy of Thomas Hyde's Bodleian Library catalogue (Bodleian Locke 16.17), which Locke used to create a catalogue of his ain library.[103]

Writing

List of major works

- 1689. A Letter of the alphabet Concerning Toleration.

- 1690. A Second Letter Apropos Toleration

- 1692. A Third Letter for Toleration

- 1689/xc. Two Treatises of Government (published throughout the 18th century by London bookseller Andrew Millar past committee for Thomas Hollis)[104]

- 1689/ninety. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

- 1691. Some Considerations on the consequences of the Lowering of Involvement and the Raising of the Value of Coin

- 1693. Some Thoughts Concerning Education

- 1695. The Reasonableness of Christianity, as Delivered in the Scriptures

- 1695. A Vindication of the Reasonableness of Christianity

Major posthumous manuscripts

- 1660. Commencement Tract of Regime (or the English Tract)

- c.1662. Second Tract of Government (or the Latin Tract)

- 1664. Questions Concerning the Police force of Nature.[105]

- 1667. Essay Apropos Toleration

- 1706. Of the Acquit of the Understanding

- 1707. A paraphrase and notes on the Epistles of St. Paul to the Galatians, ane and 2 Corinthians, Romans, Ephesians

See likewise

- List of liberal theorists

References

Notes

- ^ Kenyon (1977) adds: "Any unbiassed study of the position shows in fact that it was Filmer, not Hobbes, Locke or Sidney, who was the most influential thinker of the age" (p. 63).

Citations

- ^ Fumerton, Richard (2000). "Foundationalist Theories of Epistemic Justification". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ David Bostock (2009). Philosophy of Mathematics: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 43.

All of Descartes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume supposed that mathematics is a theory of our ideas, just none of them offered any argument for this conceptualist merits, and manifestly took it to be uncontroversial.

- ^ John W. Yolton (2000). Realism and Appearances: An Essay in Ontology. Cambridge University Press. p. 136.

- ^ "The Correspondence Theory of Truth". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2020.

- ^ Grigoris Antoniou; John Slaney, eds. (1998). Advanced Topics in Bogus Intelligence. Springer. p. 9.

- ^ Vere Claiborne Chappell, ed. (1994). The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Cambridge Academy Press. p. 56.

- ^ a b Uzgalis, William (i May 2018) [September two, 2001]. "John Locke". In Due east. N. Zalta (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Fallacies : classical and contemporary readings. Hansen, Hans V., Pinto, Robert C. Academy Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State Academy Press. 1995. ISBN978-0-271-01416-6. OCLC 30624864.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Locke, John (1690). "Volume Four, Chapter XVII: Of Reason". An Essay Apropos Human Understanding . Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). 2 Treatises of Government (10th edition): Chapter II, Section 6. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Broad, Jacqueline (2006). "A Adult female's Influence? John Locke and Damaris Masham on Moral Accountability". Journal of the History of Ideas. 67 (3): 489–510. doi:10.1353/jhi.2006.0022. JSTOR 30141038. S2CID 170381422.

- ^ Hirschmann, Nancy J. (2009). Gender, Class, and Freedom in Modernistic Political Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 79.

- ^ Sharma, Urmila; S. K. Sharma (2006). Western Political Idea. Washington: Atlantic Publishers. p. 440.

- ^ Korab-Karpowicz, West. Julian (2010). A History of Political Philosophy: From Thucydides to Locke. New York: Global Scholarly Publications. p. 291.

- ^ Becker, Carl Lotus (1922). The Declaration of Independence: a Study in the History of Political Ideas. New York: Harcourt, Brace. p. 27.

- ^ Foreword and study guide to John Locke'due south 2 Treatises on Government: A Translation into Modern English, ISR Publications, 2013, folio ii. ISBN 9780906321690

- ^ Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 527–29. ISBN978-0-xiii-158591-1.

- ^ Broad, C. D. (2000). Ethics And the History of Philosophy. U.k.: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-22530-4.

- ^ Roger Woolhouse (2007). Locke: A Biography. Cambridge University Printing. p. 116.

- ^ Henning, Basil Duke (1983), The House of Commons, 1660–1690, vol. 1, ISBN978-0-436-19274-6 , retrieved 28 August 2012

- ^ Laslett 1988, III. 2 Treatises of Government and the Revolution of 1688.

- ^ Rebecca Newberger Goldstein (2006). Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave United states of america Modernity. New York: Schocken Books. pp. 260–61.

- ^ Rogers, Graham A. J. "John Locke". Britannica Online . Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Hoppit, Julian (2000). A Country of Liberty? England. 1689–1727. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 195.

- ^ a b Kenyon, John (1977). Revolution Principles: The Politics of Party. 1689–1720. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing.

- ^ Milton, John R. (2008) [2004]. "Locke, John (1632–1704)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16885. (Subscription or United kingdom public library membership required.)

- ^ "The Three Greatest Men". American Treasures of the Library of Congress. Library of Congress. August 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

Jefferson identified Bacon, Locke, and Newton as "the 3 greatest men that accept ever lived, without any exception". Their works in the physical and moral sciences were instrumental in Jefferson'south teaching and world view.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas. "The Messages: 1743–1826 Bacon, Locke, and Newton". Archived from the original on 31 December 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

Salary, Locke and Newton, whose pictures I will problem you to have copied for me: and as I consider them as the three greatest men that take ever lived, without whatever exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical & Moral sciences.

- ^ "Jefferson called Bacon, Newton, and Locke, who had so indelibly shaped his ideas, "my trinity of the three greatest men the world had ever produced"". Explorer. Monticello. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Seigel, Jerrold (2005). The Idea of the Self: Thought and Experience in Western Europe since the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press.

- ^ Taylor, Charles (1989). Sources of the Self: The Making of Modernistic Identity. Cambridge: Harvard Academy Press.

- ^ Schultz, Duane P. (2008). A History of Modern Psychology (ninth ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomas College Educational activity. pp. 47–48. ISBN978-0-495-09799-0.

- ^ McGrath, Alister (1998). Historical Theology, An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 214–xv.

- ^ a b c Heussi 1956.

- ^ Olmstead 1960, p. 18.

- ^ Stahl, H. (1957). "Baptisten". Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German). 3 (1), col. 863

{{cite periodical}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Halbrooks, M. Thomas; Erich Geldbach; Beak J. Leonard; Brian Stanley (2011). "Baptists". Organized religion Past and Present. doi:10.1163/1877-5888_rpp_COM_01472. ISBN978-xc-04-14666-two . Retrieved ii June 2020. .

- ^ Olmstead 1960, pp. 102–05.

- ^ Olmstead 1960, p. v.

- ^ Cohen, Martin (2008), Philosophical Tales, Blackwell, p. 101 .

- ^ Tully, James (2007), An Approach to Political Philosophy: Locke in Contexts, New York: Cambridge University Printing, p. 128, ISBN978-0-521-43638-0

- ^ Farr, J. (1986). "I. 'So Vile and Miserable an Manor': The Trouble of Slavery in Locke's Political Thought". Political Theory. fourteen (2): 263–89. doi:x.1177/0090591786014002005. JSTOR 191463. S2CID 145020766. .

- ^ Farr, J. (2008). "Locke, Natural Law, and New Earth Slavery". Political Theory. 36 (four): 495–522. doi:x.1177/0090591708317899. S2CID 159542780. .

- ^ Brewer 2017, p. 1052.

- ^ Brewer 2017, pp. 1053–1054.

- ^ Brewer 2017, pp. 1066 & 1072.

- ^ a b c Locke, John (1997a). "An Essay on the Poor Constabulary". In Mark Goldie (ed.). Locke: Political Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Locke, John. [1690] 2017. Second Treatise of Regime (10th ed.), digitized by D. Gowan. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Zuckert, Michael (1996), The Natural Rights Republic, Notre Dame University Press, pp. 73–85

- ^ Wills, Garry (2002), Inventing America: Jefferson'due south Announcement of Independence, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co

- ^ Skinner, Quentin, Visions of Politics, Cambridge .

- ^ Locke, John (2009), Two Treatises on Government: A Translation into Mod English, Industrial Systems Enquiry, p. 81, ISBN978-0-906321-47-viii

- ^ "John Locke: Inequality is inevitable and necessary". Department of Philosophy The University of Hong Kong. Archived from the original (MS PowerPoint) on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ Locke, John. "2nd Treatise". The Founders Constitution. §§ 25–51, 123–26. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved ane September 2011.

- ^ Cliff, Cobb; Foldvary, Fred. "John Locke on Property". The School of Cooperative Individualism. Archived from the original on fifteen March 2012. Retrieved fourteen October 2012.

- ^ Locke, John (1691), Some Considerations on the consequences of the Lowering of Involvement and the Raising of the Value of Money, Marxists .

- ^ a b Vaughn, Karen (1978). "John Locke and the Labor Theory of Value" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 2 (4): 311–26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2011.

- ^ Locke 1997b, p. 307.

- ^ Locke 1997b, p. 306.

- ^ The American International Encyclopedia, vol. 9, New York: JJ Footling Co, 1954 .

- ^ Angus, Joseph (1880). The Handbook of Specimens of English Literature. London: William Clowes and Sons. p. 324.

- ^ "Clarke [née Jepp], Mary". Oxford Lexicon of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Printing. doi:x.1093/ref:odnb/66720. (Subscription or United kingdom public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Locke 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Locke 1997b, p. 357.

- ^ "Dreaming, Philosophy of – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". utm.edu.

- ^ Forster, Greg (2005), John Locke's politics of moral consensus .

- ^ Parker, Kim Ian (2004), The Biblical Politics of John Locke, Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion .

- ^ Locke, John (2002), Nuovo, Victor (ed.), Writings on religion, Oxford .

- ^ a b Marshall, John (1994), John Locke: resistance, faith and responsibility, Cambridge, p. 426 .

- ^ Wainwright, Arthur, West., ed. (1987). The Clarendon Edition of the Works of John Locke: A Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistle of St. Paul to the Galatians, i and 2 Corinthians, Romans, Ephesians. Oxford: Clarendon Printing. p. 806. ISBN978-0-19-824806-4.

- ^ Waldron 2002, pp. 27, 223.

- ^ Nelson 2019, pp. seven–8.

- ^ Waldron 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Henrich, D (1960), "Locke, John", Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German) , 3. Auflage, Band Four, Spalte 426

- ^ Waldron 2002, pp. 217 ff.

- ^ a b Waldron 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Dunn, John (1969), The Political Thought of John Locke: A Historical Account of the Statement of the 'Two Treatises of Authorities' , Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p. 99,

[The Two Treatises of Government are] saturated with Christian assumptions.

. - ^ Wolterstorff, Nicholas. 1994. "John Locke's Epistemological Piety: Reason Is The Candle Of The Lord." Organized religion and Philosophy xi(4):572–91.

- ^ Waldron 2002, p. 142.

- ^ Elze, M (1958), "Grotius, Hugo", Die Faith in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German language) two(iii):1885–86.

- ^ Hohlwein, H (1961), "Pufendorf, Samuel Freiherr von", Dice Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German) , 5(3):721.

- ^ Waldron 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Waldron 2002, pp. 22–43, 45–46, 101, 153–58, 195, 197.

- ^ Waldron 2002, pp. 21–43.

- ^ Waldron 2002, p. 136.

- ^ Locke, John (1947). Two Treatises of Government. New York: Hafner Publishing Company. pp. 17–18, 35, 38.

- ^ Becker, Carl. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. 1922. Google Book Search. Revised edition New York: Vintage Books, 1970. ISBN 978-0-394-70060-one.

- ^ Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. one.

- ^ a b c d Quoted in Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 8.

- ^ Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 57–61.

- ^ a b c d Bodleian Library. "Rare Books Named Collections".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 20.

- ^ Harrison, John; Laslett, Peter (1971). The Library of John Locke. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e Clapinson, M, and TD Rogers. 1991. Summary Catalogue of Post-Medieval Western Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Vol. 2. Oxford University Printing.

- ^ The works of Robert Boyle, vol. 12. Edited by Michael Hunter and Edward B. Davis. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2000, pp. xviii–xxi.

- ^ James Farr and Clayton Robers. "John Locke on the Glorious Revolution: a Rediscovered Document" Historical Journal 28 (1985): 395–98.

- ^ Richard Yeo, Notebooks, English Virtuosi (University of Chicago Press, 2014), 183.

- ^ John Locke, The Educational Writings of John Locke, ed. James Axtell (Cambridge University Press, 1968), 421.

- ^ Richard Yeo, Notebooks, English language Virtuosi (Academy of Chicago Press, 2014), 218.

- ^ G. Grand. Meynell, "John Locke'southward Method of Common-Placing, every bit seen in His Drafts and His Medical Notebooks, Bodleian MSS Locke d. ix, f. 21 and f. 23," The Seventeenth Century 8, no. ii (1993): 248.

- ^ Michael Stolberg, "John Locke's 'New Method of Making Common-Place-Books': Tradition, Innovation and Epistemic Furnishings," Early Science and Medicine nineteen, no. 5 (2014): 448–70.

- ^ John Locke, A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books (London: Printed for J. Greenood, 1706), 4.

- ^ G. Grand. Meynell, "A Database for John Locke's Medical Notebooks and Medical Reading," Medical History 42 (1997): 478

- ^ "The manuscripts, Letter of the alphabet from Andrew Millar to Thomas Cadell, sixteen July, 1765. University of Edinburgh". www.millar-projection.ed.ac.uk . Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ Locke, John. [1664] 1990. Questions Concerning the Constabulary of Nature (definitive Latin text), translated by R. Horwitz, et al. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Sources

- Ashcraft, Richard, 1986. Revolutionary Politics & Locke's Two Treatises of Authorities. Princeton: Princeton University Printing. Discusses the human relationship between Locke's philosophy and his political activities.

- Ayers, Michael, 1991. Locke. Epistemology & Ontology Routledge (the standard work on Locke's Essay Concerning Homo Agreement.)

- Bailyn, Bernard, 1992 (1967). The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Harvard Uni. Press. Discusses the influence of Locke and other thinkers upon the American Revolution and on subsequent American political idea.

- Brewer, Holly (Oct 2017). "Slavery, Sovereignty, and "Inheritable Blood": Reconsidering John Locke and the Origins of American Slavery". American Historical Review. 122 (4): 1038–1078. doi:10.1093/ahr/122.four.1038.

- Cohen, Gerald, 1995. 'Marx and Locke on Land and Labour', in his Self-Buying, Freedom and Equality, Oxford University Press.

- Cox, Richard, Locke on War and Peace, Oxford: Oxford University Printing, 1960. A discussion of Locke's theory of international relations.

- Chappell, Vere, ed., 1994. The Cambridge Companion to Locke. Cambridge U.P. excerpt and text search

- Dunn, John, 1984. Locke. Oxford Uni. Press. A succinct introduction.

- ———, 1969. The Political Thought of John Locke: An Historical Account of the Statement of the "Two Treatises of Government". Cambridge Uni. Press. Introduced the interpretation which emphasises the theological chemical element in Locke'due south political thought.

- Heussi, Karl (1956), Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte (in German), Tübingen, DE

- Hudson, Nicholas, "John Locke and the Tradition of Nominalism," in: Nominalism and Literary Discourse, ed. Hugo Keiper, Christoph Bode, and Richard Utz (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1997), pp. 283–99.

- Laslett, Peter (1988), Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press to Locke, John, Ii Treatises of Government

- Locke, John (1996), Grant, Ruth W; Tarcov, Nathan (eds.), Some Thoughts Concerning Education and of the Conduct of the Understanding, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co, p. 10

- Locke, John (1997b), Woolhouse, Roger (ed.), An Essay Concerning Homo Understanding, New York: Penguin Books

- Locke Studies, appearing annually from 2001, formerly The Locke Newsletter (1970–2000), publishes scholarly work on John Locke.

- Mack, Eric (2008). "Locke, John (1632–1704)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Grand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Found. pp. 305–07. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n184. ISBN978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Macpherson, C.B. The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962). Establishes the deep affinity from Hobbes to Harrington, the Levellers, and Locke through to nineteenth-century utilitarianism.

- Moseley, Alexander (2007), John Locke: Continuum Library of Educational Thought, Continuum, ISBN978-0-8264-8405-v

- Nelson, Eric (2019). The Theology of Liberalism: Political Philosophy and the Justice of God. Cambridge: Harvard University Printing. ISBN978-0-674-24094-0.

- Olmstead, Clifton E (1960), History of Organized religion in the United states, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

- Robinson, Dave; Groves, Judy (2003), Introducing Political Philosophy, Icon Books, ISBN978-1-84046-450-four

- Rousseau, George Due south. (2004), Nervous Acts: Essays on Literature, Civilisation and Sensibility, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN978-1-4039-3453-half dozen

- Tully, James, 1980. A Discourse on Property : John Locke and his Adversaries. Cambridge Uni. Printing

- Waldron, Jeremy (2002), God, Locke, and Equality: Christian Foundations in Locke's Political Thought, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN978-0-521-89057-1

- Yolton, John W., ed., 1969. John Locke: Problems and Perspectives. Cambridge Uni. Press.

- Yolton, John W., ed., 1993. A Locke Dictionary. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Zuckert, Michael, Launching Liberalism: On Lockean Political Philosophy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

External links

Works

- The Clarendon Edition of the Works of John Locke

- Of the Bear of the Understanding

- Works past John Locke at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Locke at Internet Archive

- Works past John Locke at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Work by John Locke at Online Books

- The Works of John Locke

- 1823 Edition, ten volumes on PDF files, and additional resource

- John Locke Manuscripts

- Updated versions of Essay Concerning Homo Agreement, Second Treatise of Government, Letter on Toleration and Conduct of the Understanding, edited (i.e. modernized and abridged) by Jonathan Bennett

Resource

- Rickless, Samuel. "Locke on Freedom". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "John Locke". Cyberspace Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "John Locke: Political Philosophy". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- John Locke Bibliography

- Locke Studies An Annual Journal of Locke Research

- Hewett, Caspar, John Locke'south Theory of Knowledge, United kingdom: The great debate .

- The Digital Locke Project, NL, archived from the original on one Jan 2014, retrieved 27 February 2007 .

- Portraits of Locke, Uk: NPG .

- Huyler, Jerome, Was Locke a Liberal? (PDF), Independent, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009, retrieved 2 August 2008 , a complex and positive respond.

- Kraynak, Robert P. (March 1980). "John Locke: from absolutism to toleration". American Political Science Review. 74 (1): 53–69. doi:10.2307/1955646. JSTOR 1955646.

- Anstey, Peter, John Locke and Natural Philosophy, Oxford Academy Printing, 2011.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Locke

Posting Komentar untuk "*rpp, Reading 70, Rawls, a Theory of Justice"